Sovereign debt takeaways from the IMF meetings

Sovereign debt was on top of the agenda during the IMF/WB Spring Meetings, between April 10 and 16. There was movement at the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable and at the country level for ongoing restructurings. Most of the progress remains preliminary and coming weeks will show if we are moving past the logjam that has plagued sovereign restructurings in recent years.

This blog dives into four main takeaways from the IMF/WB meetings:

Ongoing discussions about whether we are witnessing a systemic debt crisis in LICs and the subsequent policy response;

Notable movements at the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable;

How domestic debt is climbing up the policy agenda and the risks of hastened policy changes;

How global policy developments translate into movement for ongoing sovereign restructurings.

The blog post is unusually long so feel free to jump to any of the four parts.

A HIPC moment? The jury is still out

Just before the start of the Spring Meetings the IMF published a working paper with a star-studded line-up of authors, comparing the current debt situation in LICs to the pre-HIPC era. They say the following:

The main conclusion is that, high risks notwithstanding, debt vulnerabilities in low-income countries today remain substantially less alarming on average than they were in the mid-1990s. […] This said, debt vulnerabilities in LICs could reach levels comparable to those of the mid-1990s over the medium- to long-term if current trends persist and in the absence of policies and reforms to address such vulnerabilities.

This point is best summed-up with the following graphs, showing that debt levels on average, despite a sharp increase, remain lower today than pre-HIPC and sovereign arrears are yet to pick up significantly. (All graphs in this section are sourced from the IMF paper.)

This IMF paper comes at an important moment, with debates around the best way to address debt vulnerabilities in LICs, and calls for a systemic approach akin to HIPC or the Brady plan, such as the “Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery” proposal by Ulrich Volz and colleagues.

The IMF as an institution has often erred in recent months towards the idea of a systemic debt crisis in LICs, in order to stress the urgency of the required policy response. During the Spring Meetings – that is after the publication of the IMF paper – the head of the IMF Africa Department called for a “Gleneagles-like moment”, in reference to the 2005 G8 summit which gave birth to the MDRI initative to complement HIPC. Back in October the World Bank Chief Economist called for “another round of structured debt relief, because that’s what HIPC was”, similarly illustrating the institutional debates going on within the Bretton Woods institution.

While the IMF paper would tend to push back on the relevance of a blanket approach to debt relief, devil is in the detail and there is much more in the piece than the headline conclusion.

First, the absence of arrears could be the tip of the iceberg, hiding a development crisis brewing across LICs as governments service their debt at the expense of other crucial expenditures. Masood Ahmed nailed it at a recent conference:

I don’t think we are going to have many defaults - the cost of default is very high. (…) What we are going to see is that unsustainable debt service is going to lead to development crises rather than debt crises. There will be default for future generations, cutting back on investments for the future.

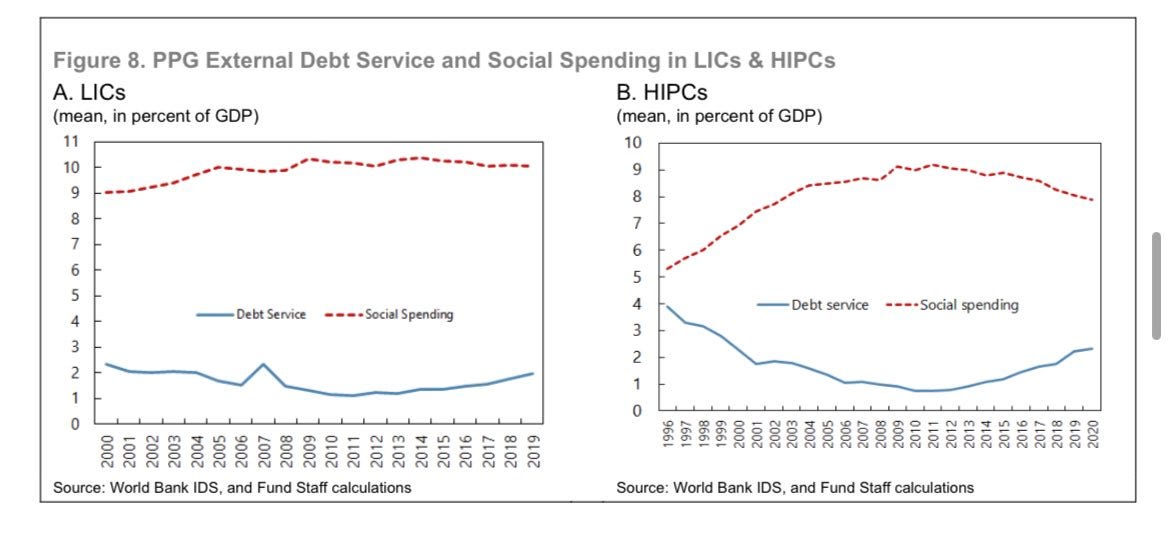

The IMF paper studies this specific point by looking at the gap between debt service and social spending in LICs. While the gap remains better than during the HIPC period, the direction of travel is especially worrying at a time when LICs face a series of shocks from the COVID-19 pandemic to the spillovers of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

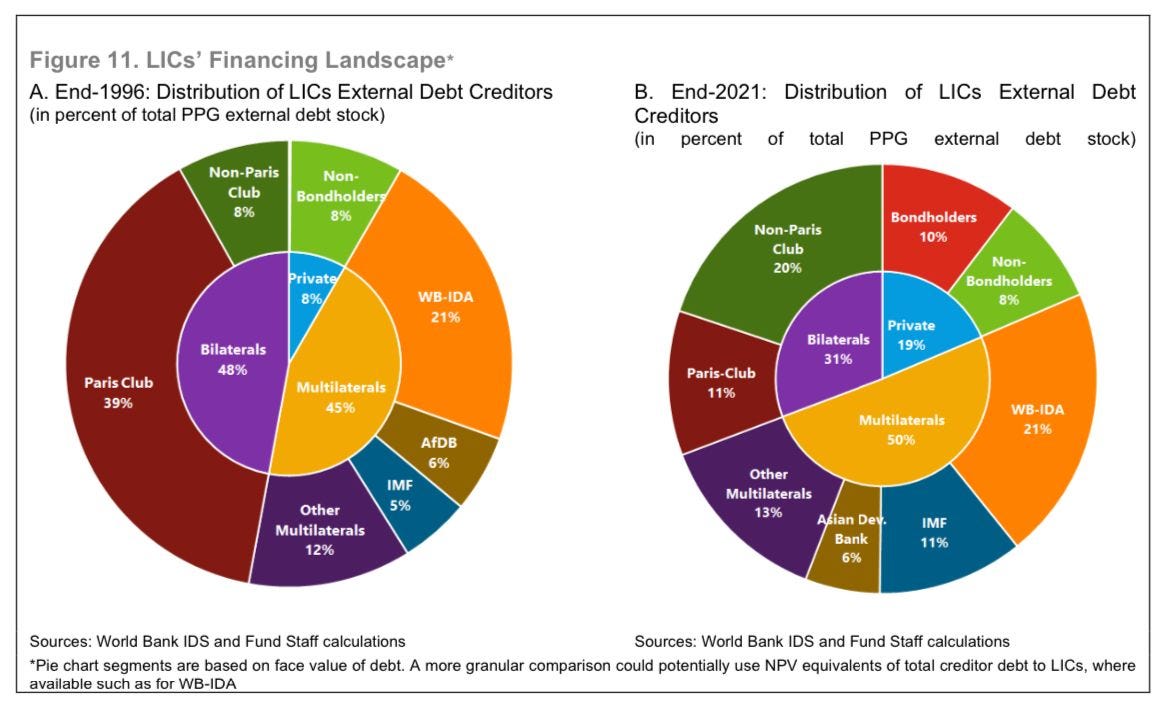

There could be several reasons for the growing cost of restructurings. First, the increased fragmentation of the creditor landscape in LICs has made the process more burdensome, delaying not only the resolution of the debt overhangs but also the provision of support by the IMF and its partners as showed recently by Jorgelina do Rosario. The graph below neatly illustrates the fragmentation by showing the increased share of non-Paris Club bilateral creditors – for which there is no streamlined process when it comes to sovereign restructurings – and bondholders in the LICs debt stock. The increased share of multilateral debt – usually excluded from restructurings – has also further rigidified debt stocks.

Second, at a granular level, the IMF notes (paragrah 29 of the paper) that the use of increasingly complex debt instruments by LICs could further deter or prevent governments from engaging in timely and preemptive restructurings – this includes the use of guarantees, securitization, collateral, and PPPs. The IMF notes:

“Debt instruments with special enhancements that go beyond the standard “plain vanilla” terms could be more difficult to manage and assess risks and, when they are collateralized and guaranteed, they could easily be transferred to the sovereign’s balance sheet in the face of sudden economic shocks, thereby elevating debt vulnerabilities and complicating debt treatments.”

All these factors, combined with stalemates observed in countries such as Zambia, are significantly reducing the incentives of governments to restructure or default, potentially leading to hard defaults and worse outcomes later on.

However, if push comes to shove and we do reach that HIPC moment, the IMF already warns of donor fatigue as a major hurdle towards the implementation of the policy response. This is underscored by the graph below showing that net flows to LICs as a percentage of GDP have plateaued in the wake of HIPC. The outlook is gloomy at best, with Chinese lending declining, market access hampered across the board, aid budgets under threat in advanced economies, and protracted debates about ways to increase the firepower of IFIs. As showed by Brad Setser, net flows to developing economies will “fall off a cliff” absent a dramatic change of course.

It will be interesting to watch in coming months which view prevails within the IMF and the World Bank when it comes to the relevance of a structured wave of debt relief, and whether it is merely a descriptive disagreement or it shapes the response of these institutions to debt crises in LICs.

Progress at the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable

From the start of the Spring Meetings, the sovereign debt crowd was abuzz with talks of a potential compromise between China and other stakeholders to break the sovereign debt restructuring logjam. The WSJ first came out, indicating China could drop its demand for MDBs to take haircuts in exchange for fresh MDB funding during restructurings. Then came Reuters saying that in exchange for dropping its demand China would get earlier access to the IMF’s DSA during restructurings.

The co-chairs of the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR) finally published a statement on Wednesday April 12 which provides interesting insights on the current state of play. The discussions seem to be structured around a three-pronged approach involving:

Increased transparency and information sharing for the IMF/WB DSA;

An agreement on the way to assess comparability of treatment across creditors;

Increased efforts by MDBs through “net positive flows”.

One then has to read between the lines of the communiqué to understand the concrete progress and potential policy changes.

First, with regards to information sharing, the mention that the IMF will issue staff guidance seems to indicate that there will be no sea change – any significant policy modification would require to go through the Executive Board. “Staff guidance” hence means that the IMF will probably encourage mission chiefs to do the most they can within existing rules. This falls short of China’s demand to provide inputs in the IMF DSA, and that of commercial creditors to have access to the full DSA between the staff-level agreement and the Board approval. However, the IMF arguably wants to protect the value of the involvement of its Executive Board: the role of IMF DSAs comes from the fact that they are approved by the IMF Board giving them their legitimacy. It is unsure as a result whether all stakeholders will come to an agreement soon.

Second, the outcomes of the workshop on comparability of treatment (CoT) will be interesting to watch, especially the attitude of the Paris Club. The Club currently assesses CoT in a holistic manner involving three different measures, and has never withdrawn a restructuring agreement due to a breach of CoT as noted by Diego Rivetti. Choosing one definitive measure of CoT could corner the Paris Club, blowing up any restructuring agreement if China or bondholders then strike a deal on slightly better terms according to the set formula, even if the difference is negligible.

Finally, the most important point of the GSDR communiqué is the role of MDBs in restructurings. It is difficult at this stage to understand whether any concrete progress has been made. The head of the SPR department at the IMF went on the record talking about a “major breakthrough” and indicating haircuts for MDBs were now off the table. However, the tone of Chinese officials was more muted to say the least – their public remarks do not indicate a major change of stance for now.

As a further illustration of cautiousness, in the wake of the IMF meetings Janet Yellen gave remarks at SAIS on the US-China economic relationship and told the audience that China “has served as a roadblock to necessary action”, without mentioning the GSDR or any progress in policy discussions.

The definition itself of net positive flows from MDBs is not totally clear, and we can expect tough discussions on whether it should be made up mostly of grants or loans, in which proportion, etc. It will be also interesting to see whether the discussion of MDBs support in restructurings becomes one piece of the broader debate around the increase of the MDBs’ firepower, including through a reform of their capital adequacy frameworks.

The reason for the uncertainty on this topic is probably that the heavy lifting is yet to come – even if haircuts are off the table – as the definition of the “additional effort” by MDBs entails major hurdles. First, MDBs other than the World Bank were not at the table in GSDR discussions, yet they would be binded by the resulting arrangement. Second, the ability of MDBs to provide outright grants – which China might consider as the closest equivalent to a participation in restructurings – is limited. Third, MDBs are constrained by their internal policies including country envelopes, which might prevent them from extending additional support to some countries undergoing restructurings.

The GSDR appears to be a meaningful forum for a broad dialogue, and has touched upon many contentious issues that had been somewhat avoided in recent years. However, we have to aknowledge that the gap remains significant on many fundamental debates and concrete progress is yet to materialize.

Finally, the GSDR communiqué already indicates other topics to be discussed in the upcoming gatherings: “cut-off dates, formal debt service suspension at the beginning of the process, treatment of arrears, and perimeter of debt to be restructured, including with regards to domestic debt”.

The perimeter issue will be one to watch, including when it comes to the treatment of central bank swaps in restructurings. The inclusion of these instruments in the perimeter remains rather untested in recent years but might come back to the limelight – a recent paper by Sebastian Horn and colleagues provides early evidence of China bailing out loans extended by its policy banks through the use of swaps with the PBoC. Other creditors might hence push for these swaps to be restructured to satisfy fair burden sharing.

The domestic debt puzzle

Among the topics to be discussed further by the GSDR, domestic debt stands out as especially important. It has been climbing up the policy agenda in recent months and featured predominantly in policy discusions at the IMF meetings, especially as governments shut out of international capital markets rely increasingly on domestic markets to finance their budget. This has already led the IMF to dedicate a chapter of the Global Financial Stability Report to the sovereign-bank nexus in emerging markets.

Domestic debt has also been an important topic in ongoing restructurings. Looking at the sequence of events in recent months:

Zambia first chose in 2022 to exclude domestic-currency debt from the perimeter of its restructuring given '“material spillover risks” (para. 28 of the IMF staff report).

Ghana then implemented a domestic debt restructuring in Q1 2023 before starting negotiations with its external creditors.

Subsequently, bondholders demanded in a letter to the IMF Managing Director that Sri Lanka “reorganize” its domestic debt as part of the ongoing restructurings. A few weeks later the authorities announced in a creditor presentation that they would implement a “domestic debt optimization”.

While we can see an early trend towards the inclusion of domestic debt in restructurings, this process is no quiet river. Ghana is working on the implementation of a financial stability fund to alleviate any impact of the domestic restructuring on its banking sector, and press reports indicate that Sri Lanka is facing hurdles with its voluntary domestic debt restructuring.

In Zambia, domestic debt came back to bite as the foreign holdings of domestic debt excluded from the restructuring were nonetheless included in the IMF external DSA, conducted on a residency criteria, and hence eat up the country’s debt servicing capacity in the short term within the DSA – something Brad Setser has written about in depth.

Although the international financial architecture is blatantly ill-equipped to deal with growing domestic debt markets and foreign participation in them, any blanket approach to burden sharing between external and domestic debt remains at best elusive, at worst detrimental to all stakeholders.

Anna Gelpern and Brad Setser made a compelling argument in this view in a 2004 paper entitled “Domestic and External Debt: The Doomed Quest for Equal Treatment”. They wrote that a systematic approach to domestic debt treatment is probably not desirable since it would not unfold in the context of a matching social safety net. In essence, such a systematic approach would surely fail to capture the broader relationship between a sovereign debtor and its domestic creditors, since it involves for example the provision of social security, education, the supervision of the financial sector, etc.

Anna and Brad’s argument was framed in the context of debates around the creation of a Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism (SDRM). Interestingly enough, a paper published around that time by the IMF touched specifically upon the potential inclusion of domestic debt in the SDRM, and indicated (para. 42) that “consultations with foreign investors to date suggest that they would actually prefer to have domestic debt excluded from the SDRM”.

The IMF’s doctrine so far on domestic debt restructurings has been prudent and sensible, as illustrated by the 2021 primer and subsequent blog rightly entitled “handle with care”. One would hope the doctrine remains somewhat the same, assessing costs and benefits on a case-by-case basis and rebuking calls for a systematic burden sharing incolving domestic debt.

Finally, the issue is much wider than restructurings: in recent years the IMF and the WB have provided significant technical assistance to help countries develop their domestic debt markets and attract foreign investors, notably to reduce the exposure to foreign currency risks. Any policy change regarding the inclusion of domestic debt in restructurings will need to take this aspect into account. Indeed, a more regular inclusion of domestic debt in restructurings could significantly impact market dynamics or foreign investors’ behaviors when debt vulnerabilities increase.

Moving pieces at the country level

Progress at the country-level is probably the best way to judge any movement and progress in global policy discussions. The IMF meetings provided some rather positive developments across the board. For instance, Ethiopia is moving towards an IMF program which would lay ground for a subsequent debt treatment that the country requested through the G20 Common Framework.

Bondholders are apparently becoming more proactive and seem eager to strike faster restructuring deals despite potential stalemates in negotiations with bilateral official creditors:

Bloomberg reported that Suriname is nearing a restructuring agreement with commercial creditors, which will be interesting to watch with regards to the inclusion of commodity-linked instruments.

Reuters reported that Zambia sent a concrete restructuring proposal to bondholders.

Reuters reported that Sri Lanka’s bondholders sent a first restructuring proposal to the authorities.

Though these are steps in the right direction, we are yet to witness the signing of a definitive restructuring agreement with bondholders in any of the major cases. Additionally, these developments contrast sharply with the absence of major progress or even movement when it comes to bilateral creditors and especially China.

A first indication of China’s behavior can be found in Sri Lanka, where all the other major bilateral creditors announced the creation of a common forum for restructuring discussions, without China so far. Despite providing financing assurances to the IMF a few weeks earlier, China either does not yet want to negotiate, or prefers to do so in a bilateral manner, which would again trigger questions around comparability of treatment.

Zambia, finally, is the prominent test-case for the ability of China to start discussing concrete restructuring terms, and the IMF program’s first review and disbursement remain up in the air absent any progress on the restructuring front. As I wrote earlier, the IMF faces a difficult trade-off between appearing to let down Zambia which implemented all required policies, and reducing the incentive for China to play ball in the restructuring if it disburses without progress.

The IMF indicated that the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) would be sufficient to unlock the review. The Zambian authorities hinted during the IMF meetings that they hope significant progress towards the MoU, even if it is not signed, would enable the IMF to make the disbursement anyway.

In addition, depending on its content, the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) could amount to kicking the can down the road. As with Paris Club agreements, such an MoU is “legally non-binding” – what matters is the subsequent bilateral agreement signed between the debtor country and each creditor. This means that China could in theory sign the MoU and then drag its feet when it comes to turning it into a concrete restructuring deal for all Chinese claims. This would threaten a replay of the current stand-off during all remaining program reviews.

There is cause for concern, as a similar pattern was observed with financing assurances: the IMF accepted somewhat vague financing assurances from China which turned out to be anything but “specific and credible”, as China subsequently pushed back on the assumptions of the IMF program and DSA instead of negotiating restructuring terms in line with these parameters.

The problem is reinforced by the lack of transparency and guidelines of the G20 Common Framework. Nobody knows what a Common Framework MoU looks like – the one for Chad, the only one signed so far, was not published. It would hence be positive for the IMF and G20 members to provide additional transparency about what parameters should be detailed in a MoU.

These are difficult discussions but it does not seem for now that they can be avoided, as the alternatives – including the use of the IMF arrears policies – remain at best temporary fixes. Despite the hurdles, China’s presence at the GSDR and the depth of discussions in recent weeks do provide room for cautious hope. Once again, any progress will only be assessed properly if the transparency of the process is increased across the board.

I am grateful to Bernat Adrogue, Mathilde gassies and Stephen Paduano for valuable comments.

If you want to discuss this further, please reach out: tmaret@globalsov.com

You can also follow me on twitter @TheoMaret