The cautionary tale of Zambia's domestic debt

The architecture for sovereign debt restructurings tends to be shaped by landmark cases. In that view, the deal reached in June by Zambia with its Official Creditor Committee is an important milestone. One aspect that ought to get more attention however is the story of Zambia’s domestic debt since the country’s external default in November 2020.

Domestic debt has long been a missing piece in the international financial architecture, and Zambia has been a case in point. IMF support was withheld for almost two years absent financing assurances from official creditors, leading Zambia to rely heavily on its domestic debt market. This coincided with massive foreign inflows over the summer of 2021, supported by various factors (SDR allocation, election).

The inclusion of these nonresident holdings in the IMF’s external DSA then created pressures from other creditors to try and sweep them into the restructuring perimeter. Fears of a potential domestic debt restructuring in turn led to cracks appearing in the local market, until official creditors stated publicly that they would leave domestic debt untouched as part of their restructuring deal.

For all the policy debates about whether domestic debt should be included in sovereign restructurings, including a dedicated GSDR workshop on Friday, this blog takes a reverse perspective and tries to show how the current architecture for sovereign restructurings creates unproductive dynamics in domestic debt markets — be it overreliance by governments, volatile flows, or misplaced incentives to include domestic debt in the perimeter.

Domestic debt as a last resort when international support falls short

Zambia defaulted in November 2020 on its external debt, and requested a debt treatment under the G20 Common Framework in February 2021. It then took a year and a half for official creditors to provide financing assurances to the IMF, in August 2022 — the IMF program was only approved in September 2022, almost two years after Zambia’s default. Something often overlooked: not only was IMF support withheld during that period but also that of other development partners, many of whom require an IMF upper-credit tranche program in place to make significant disbursements.

Embroiled in geopolitical battles that were none of its making, the Zambian government had to find other avenues to plug financing gaps, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic which required additional expenditures across the board.

A first source of financing came from the global allocation of Special Drawing Rights by the IMF, of which Zambia received the equivalent of $1.3 billion. Zambia was, in relative terms, one of the main beneficiaries of this allocation. S&P noted the following in June 2021:

We still judge that for five sovereigns it will be enough to sufficiently bring reserves to a level at which all adequacy benchmarks will be newly satisfied. This group includes Zambia (the gross reserves of which will more than double), Jordan, El Salvador, Benin, and Togo.

The SDR allocation supported Zambia’s social spending in the wake of the pandemic and the crisis that was exacerbated by the default, according to the IMF’s 2023 staff report:

The government used about 50 percent of the proceeds to finance the 2022 Budget, mostly for social sector spending including the social cash transfer programme and pension arrears clearance.

However, beyond the one-off SDR allocation, the main source of funding for Zambia was the domestic debt market. As the IMF notes in the same report:

The domestic debt stock (Government securities) increased as external financing remained constrained. The stock of Government securities was K210.0 billion at end-2022, an increase of 9.0 percent from K192.9 billion as at end-December 2021.

This is obviously a more generic trend across frontier economies cut off from international capital markets after the pandemic — the IMF wrote in a chapter of the April 2022 GFSR that “the additional government financing needs have been met mostly by domestic banks amid declining foreign participation in local currency bond markets”.

What makes Zambia specific however is that the reliance on the domestic market was supported by sudden and massive inflows from foreign investors, compelled in the summer of 2021 by the improved macroeconomic outlook, the appreciation of the kwacha, the election of a new president viewed as a reformist and fiscally responsible, as well as the improvement of the external position by the SDR allocation.

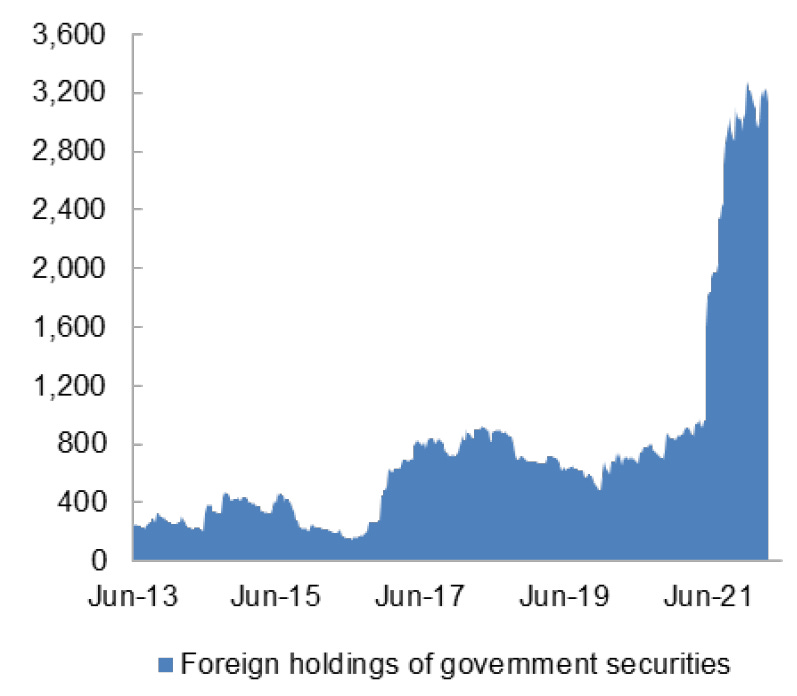

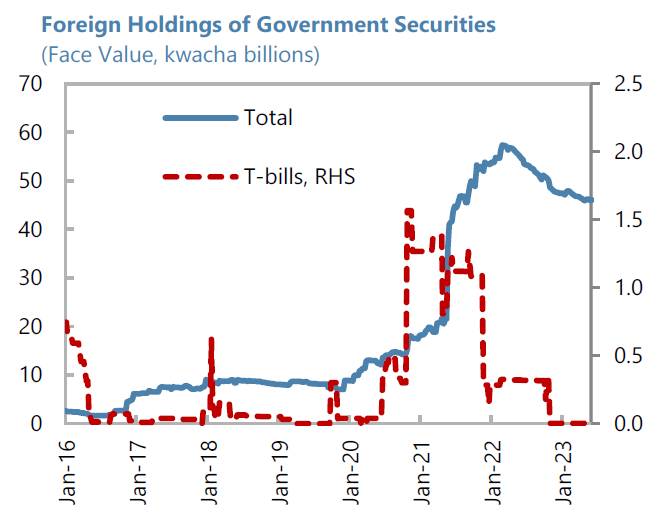

As a result, over the course of barely two-three months, nonresident holdings (NRH) of domestic debt skyrocketed in face value, from c. $800 million to more than $3 billion. The inflows are particularly visible on this chart from the IMF September 2022 staff report:

As the IMF sums up in the 2023 staff report:

The 2022 deficit was equally financed by the domestic market (1/3), ongoing project-financing together with additional IMF and WB resources (1/3), and use of half the 2021 SDR allocation (1/3).

Bottom line, the IMF’s inability to disburse rapidly is pushing debtor countries towards suboptimal borrowing decisions, draining their one-off SDR allocation (hence incurring a permanent liability to the IMF at a variable interest rate, higher for instance than the 0% of IMF PRGT loans), repurposing badly needed project loans for emergency spending, and once these sources dry up, over relying on often thin domestic debt markets.

In addition, Zambia’s ability to tap foreign investors on a significant scale in the local market was predicated on events that were out of its control — macroeconomic outlook improvement, elections, historic SDR allocation — which means that other countries undergoing a restructuring could instead end up saddling their domestic banking system with government debt.

Furthermore, it is not totally clear that volatile portfolio inflows in the domestic debt market are the adequate source of financing for countries in the wake of a sovereign default, as opposed to cheaper long-term concessional financing which can better anchor the recovery. And indeed, these NRH would come back to bite.

Blurred lines between domestic and external debt

When the IMF program was approved in September 2022 and restructuring negotiations started, Zambia’s authorities made it clear from the start that they would exclude local-currency debt from the restructuring altogether, out of concerns for financial stability in the domestic banking sector. As the IMF duly noted in the 2022 staff report:

Given the material spillover risks, the authorities intend to exclude domestically-issued debt from the restructuring perimeter. Domestically-issued debt accounts for 48 percent of GDP and represents the most significant source of budget financing in the near to medium term. While non-residents hold about 26 percent of this stock, the Zambian financial sector holds the bulk. In particular, these securities account for almost one third of banking sector assets (or about 12 percent of GDP). Therefore, any restructuring of this debt could trigger significant financial instability, potentially requiring public resources to support the sector. It would also raise broader economic risks by weakening market and business confidence, triggering capital outflows, and reducing the private sector’s access to finance.

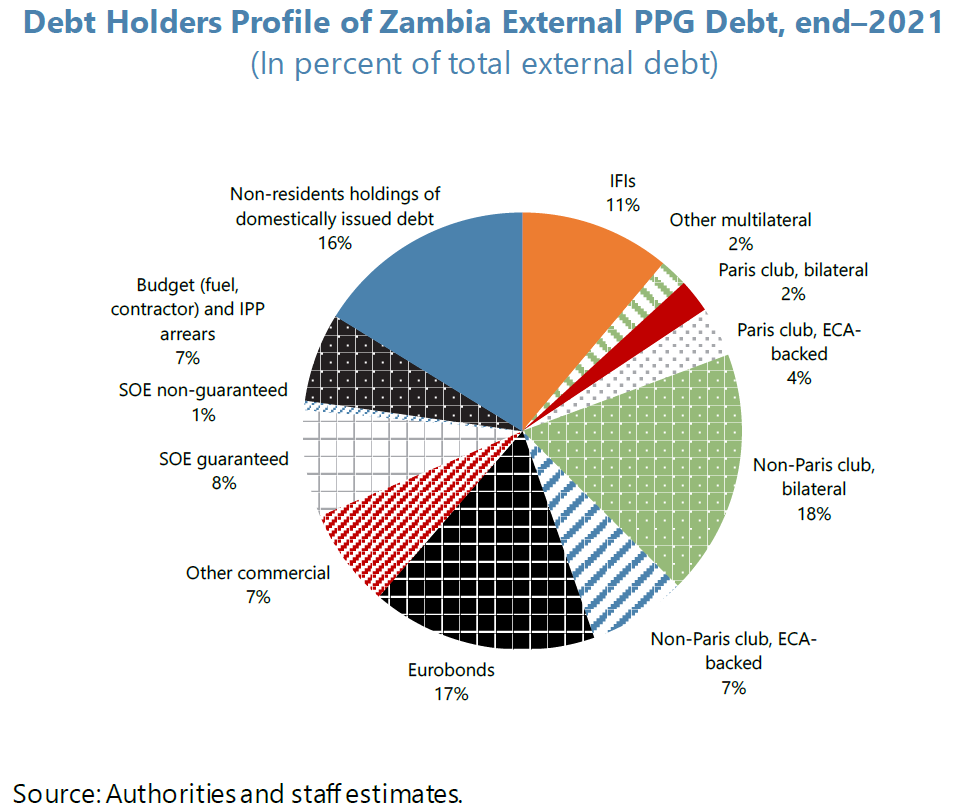

However, the IMF’s DSA for Zambia is conducted according to the model for low-income countries (LIC-DSF), based on a residency criterion — as opposed to currency. This meant all the local-currency debt held by non-resident had to be included in the external debt stock, creating a sharp discrepancy between the scope of the DSA and that of the restructuring. NRH were estimated by the IMF at $3.2 billion in face value, as big as the outstanding stock of Eurobonds.

Heres the external debt breakdown from the IMF 2022 staff report:

This decision was bound to create inter-creditor tensions: the definition of the restructuring envelope from the IMF’s DSA is a zero-sum game, meaning any increase in non-restructurable debt in the external debt stock automatically translates in additional debt relief requirements from other creditors — namely official bilateral creditors and Eurobond holders.

Other external creditors rapidly argued that the importance of NRH inflows was highly inflated since most of these bonds were actually issued at a discount, or then traded at a discount on the secondary market due to interest rate swings, and hence the actual inflows of foreign currency were much lower than the $3.2 billion in face taken by the IMF.

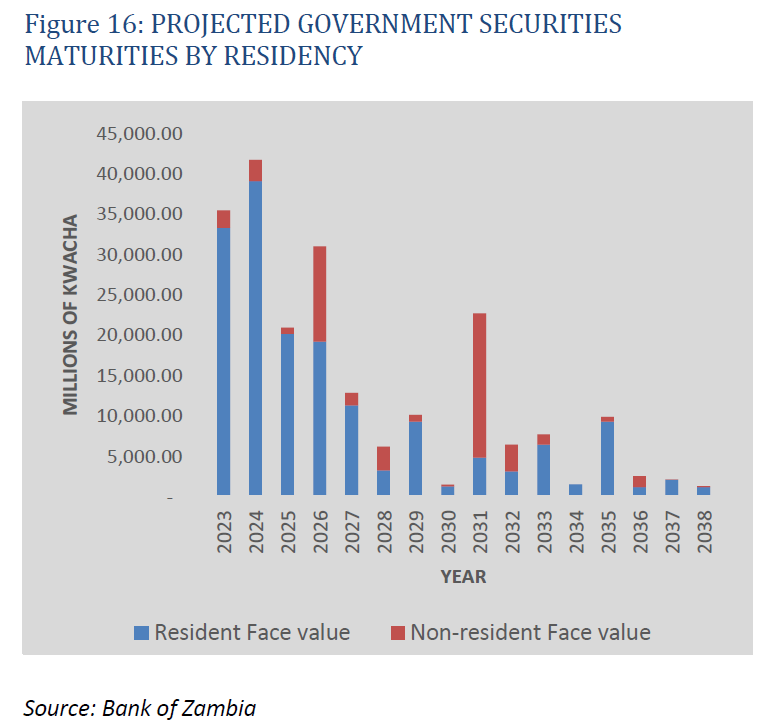

One could argue that the face value remains the most relevant indicator since this is the amount that the government will have to repay in the end. However this assumes that foreign holders hold the bond to maturity, something which the volatile inflows and outflows tend to dismiss. Especially, Zambia’s end-June 2023 debt bulletin shows that NRH are concentrated in maturities beyond one year, especially bonds due in 2026 and 2031, meaning there is a high likelihood that foreign holders would liquidate their position before maturity, at the secondary market price rather than face value.

The share of NRH in the debt stock does not tell the whole story however. Local-currency debt instruments are different from, say, Eurobonds in terms of maturity structure and nominal interest rate — for instance in its DSA assumptions the government projects that interest rates on domestic T-bills and bonds will remain in the 10-20% range for the program period.

As a result, NRH weigh even more strongly on debt service (flow) metrics than on stock metrics in the IMF’s DSA. Brad Setser has discussed this at length on his blog — bottom line in this first version of the IMF DSA NRH represented just over 15% of the external debt stock, but captured a significant share of the debt servicing capacity of Zambia in the first years of the program.

Combining data from Zambia’s DSA assumptions for NRH debt service (interest and principal) and exchange rate forecasts, and an investor presentation for available cashflows in the original DSA, one can approximate that NRH ate up just over 50% of cash flows available for debt service to all external creditors over 2022-2026. Another 32% was expected to be taken up by other debt excluded from the restructuring — multilaterals, payables, SDR allocation — meaning little remained for official creditors and Eurobond holders.

Renewed uncertainty about a potential restructuring

The IMF’s debt sustainability targets for Zambia required meaningful debt relief due to different factors: the IMF assesses Zambia to have a low debt-carrying capacity, and applies a further risk buffer of 40% on already low targets. Combined with NRH eating up most of the short-term debt servicing capacity, it soon became clear that something had to give in order for Zambia to reach a restructuring deal with official creditors and bondholders.

The IMF’s debt-carrying capacity and buffers, despite some form of judgement involved, are derived directly from the IMF’s DSA model and endorsed by the IMF Executive Board. This was virtually impossible for the IMF to change these parameters between the approval of the program and the first review. It left NRH as the only likely variable of adjustment, incentivizing “restructurable” creditors to ask Zambia to sweep NRH into the restructuring or kick them out of the DSA.

Soon enough, it was indeed reported that China was delaying a restructuring agreements by demanding a restructuring of NRH, according to US Treasury officials. Similar demands were heard from the Eurobond holders although it was less vocal.

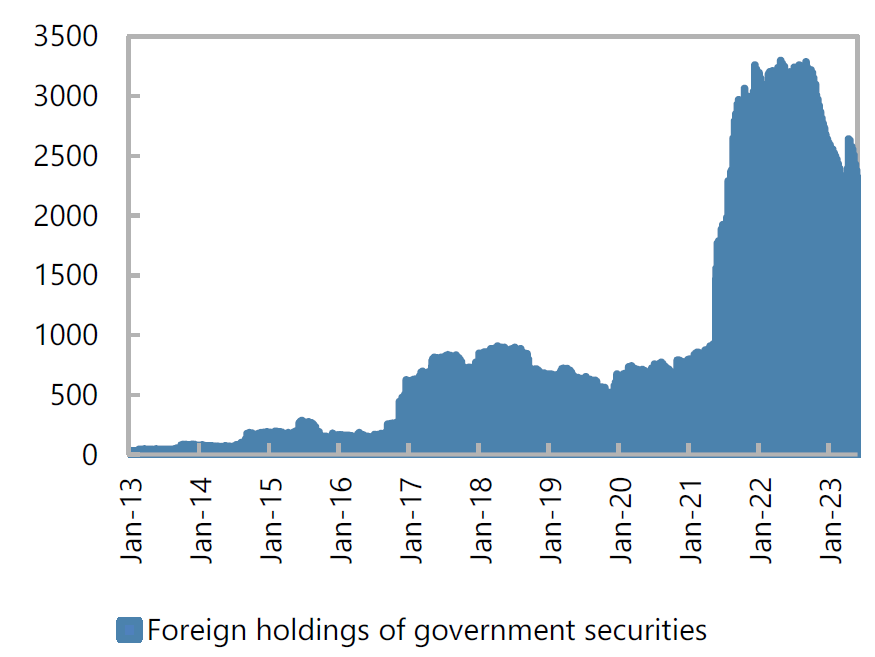

The uncertainty and discussions around a potential restructuring of NRH in turn lead to foreign outflows, draining foreign reserves and putting the currency under pressure. Outflows got the NRH down from $3.2 billion to $2.6 billion over the second half of 2022 according to the 2023 IMF staff report:

Outflows were especially sharp for T-bills, which rolled off at a faster pace than longer-dated bonds and were arguably not rolled over by nonresidents — foreign holdings of T-bills appear to now be close to zero:

The IMF acknowledges the impact of restructuring uncertainties on the exit of foreign investors from the domestic debt market:

Reflecting a combination of tighter global financial conditions and uncertainty around the debt restructuring process, non-resident investors withdrew from the domestic debt market in 2022—they did not reinvest proceeds of maturing holdings, engaged in some secondary market sales, and did not provide new inflows of funds to the market.

This underpins how IMF policies — namely the DSA residency criteria — combined with geopolitics and negotiations among external creditors had a concrete and severe impact on one of Zambia’s main sources of financing since the default, putting the economy under further strains.

Uncertainty leads to disfunctions in the domestic market

Restructuring NRH alone would have been a complex endeavor from a logistical and legal perspective, with any bond potentially held in part by domestic in part by foreign investors. The presence of domestic banks with a foreign parent company would also have caused further headache. One can go back to that 2004 paper by Anna Gelpern and Brad Setser on the “doomed quest for equal treatment” between external and domestic debt: efforts to differentiate holders by residency have never been smooth sailing.

Putting capital controls in place to limit the drain on foreign reserves of potential outflows would not have solved the conundrum either. The IMF looks at debt service figures for NRH, which do not vary whether or not at a later stage foreign investors can exchange their kwacha for USD after being repaid by the government. As a result, capital controls by themselves would probably not have removed the impact of NRH debt service on the DSA.

Therefore soon enough the issue was not only about portfolio outflows from foreign investors: since differentiating NRH from the rest of the domestic debt stock would have been difficult, pressures to restructure NRH arguably caused fears that the whole domestic debt stock would be swept into the restructuring perimeter. Coincidently during that same fall 2022 period, Ghana started its restructuring negotiations by executing a domestic debt restructuring. Similarly in early 2023 Sri Lanka announced it would execute a domestic debt optimization in order to comply with IMF debt targets, despite initially proposing to restructure only its external debt.

This in turn led domestic banks in Zambia to consider their holdings of government debt more carefully, reducing their subscription to domestic debt auctions, even more so for banks with parent companies outside of Zambia which might have been involved in Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring.

Cracks hence started to appear in the domestic debt market as a whole and the government faced increasing difficulty in raising badly needed financing. The IMF has a striking chart showing how the period of uncertainty towards the end of 2022 translates into a decrease in the bid-to-cover ratios — a sharp difference with the 800% subscription rate at the peak of inflows in the summer of 2021:

The IMF 2023 staff report sums up the materialization of funding pressures:

Average auction-cover dropped to 64 percent in 2022 and further to 45 percent January-April, from 95 percent in 2021. Demand for Treasury bills has also declined, with average auction-cover at 91 percent in 2022 and 79 percent in January-April 2023, down from 100 percent in 2021. In parallel, yields increased by around 200 basis points on average across the curve in 2022, with short-term yields rising further by about another 40 basis points on average in January-April.

Bottom line, powerplays between the IMF and creditors, especially the lack of clarity on the scope of the restructuring, contributed to disfunctions in Zambia’s domestic debt market. This is somehow even worse when considering that the Zambian government’s reliance on domestic debt as a funding source was reinforced in the first place by these same powerplays which prevented the IMF and partners from providing timely support.

Primary market restrictions as a surprising fix

Interestingly, there seems to have been a return of foreign inflows in recent months, maybe against the backdrop of hopes for a definitive resolution of the external restructuring that would spare domestic debt. NRH stood at $2.2 billion in face value at end-March 2023 according to the Q1 debt bulletin and climbed 24% over a quarter up to $2.7 billion at end-June in the Q2 debt bulletin — that is c. $100 million higher than the IMF’s estimate in its July 2023 staff report.

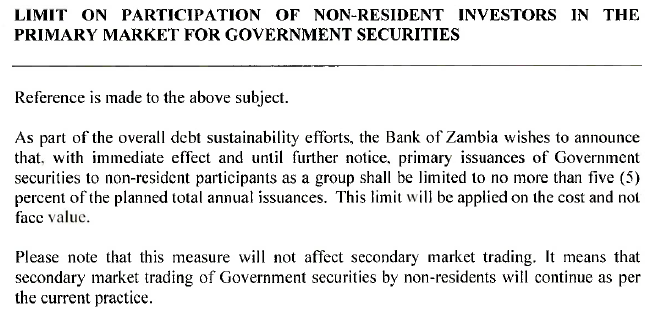

Subsequently in June 2023, the Bank of Zambia announced it would limit foreign participation in domestic debt auctions to a maximum of 5% of annual planned issuance, at face value. It seems that the restriction covers T-bills and T-bonds alike.

At first glance, it could seem like the new foreign participation limit was aimed at curbing these recent inflows and avoiding a return of the pendulum that could destabilize the economy or derail the IMF DSA. It will be interesting to gauge the impact of this measure on NRH in the next instalment of the debt bulletin in October.

However, the carve-out for secondary markets transactions will arguably limit or negate the impact of restrictions, since foreign inflows can still happen through this avenue. Domestic banks could bid for primary market auctions and sell part of their allocations directly to foreign banks and investors. If this were to happen on a significant scale, this would not only reduce the impact of the primary market restrictions but also reduce the visibility and monitoring capabilities of Zambia’s debt managers, with potential spillovers on liquidity and financing costs.

Acknowledging the restrictions would have little impact on actual market dynamics, there is a risk that they would instead window-dress IMF DSA indicators and facilitate a restructuring deal with external creditors. Coincidently, the 5% cap was announced on June 21, one day before the restructuring deal with the Official Creditor Committee.

Comparing the 2022 and 2023 IMF staff reports, there is indeed a big difference that has not been discussed much. The IMF previously expected net portfolio investments — the majority of which arguably in government securities in Zambia — to be positive every year for a total of $1.6 billion over the program period. In 2023 the IMF, noting the restriction on primary market participation, now expects negative net flows every year over 2022-2025 for a total of minus $690 million over the same period — overall a net different of more than $2 billion in portfolio flows over barely 4 years.

Similarly, the IMF originally expected debt service on NRH to be $631 million in 2023 and $439 million in 2024. In the updated data, the IMF now expects it to stand at only $445 million in 2023 and $320 million in 2024. Due to the zero-sum game aspect of restructuring negotiations, this translates into hundreds of millions in additional cashflows available for debt service to other external creditors over the program period.

Overall, it appears that real-world outflows have contributed to reduce the impact of NRH on the external debt stock, and the 5% cap on foreign participation has enabled the IMF to reduce the projected debt service on NRH in coming years, facilitating a deal with official creditors and bondholders. This is not a satisfactory solution, as the outflows put the economy under pressure and the 5% cap, as showed above, could be more about window-dressing IMF targets than any concrete benefits for Zambia.

Clarity at last, but arguably too late

When a deal was reached in June 2023 with official creditors, it was soon reported that they had agreed to leave NRH — and hence domestic debt overall — out of the restructuring. Damage, alas, had already been done as explained above.

The IMF also brought further clarity in its staff report and FAQ:

Official creditors have accepted the position of the Zambian authorities that to preserve domestic financial stability, non-resident holdings of local currency bonds and Treasury bills will not be subject to a restructuring.

Zambia’s situation was solved, albeit with blood sweat and tears, but no lasting solution for the next countries in line was found. The IMF 2023 staff report, as soon as the second paragraph, goes to great length in explaining how nothing of Zambia’s final deal would create precedents to streamline future restructurings:

These discussions covered several important issues, including […] the exclusion on non-resident holders (NRH) of domestically-issued debt from the proposed debt treatment. […] The OCC reached an agreement on all of these issues for Zambia, taking into account its specific circumstances, but official creditors recognized that these issues deserve further discussion in other cases, as well as a more systematic approach through exchanges in relevant fora.

Bottom line: a deal was done but nothing was settled.

In a further twist, the IMF in its staff report encourages the government to enact business friendly policies to attract portfolio inflows again. This seems to ignore that portfolio investment trends in recent years, as this blog tried to show, were driven in important part by exogenous factors, geopolitical powerplays and their interaction with complex IMF policies.

Lessons for the international financial architecture

Zambia’s domestic debt market has gone through a rollercoaster over the past couple years: after Zambia was let down by the international community, domestic debt was the financial lifeline that helped the country keep public services running. Then it became an unlikely sticking point in restructuring negotiations.

After shedding light on the timeline of recent years and trying to link the different factors behind the dynamics of Zambia’s domestic debt market, one can draw some more generic takeaways to inform relevant policy debates set to take place in coming months.

Time is ripe for a reform of the IMF’s arrears and financing assurances policies, ensuring the Fund can play its role in the presence of high-leverage creditors. This is obviously easier said than done, but the failure of the IMF to provide timely financial support to countries in need is leading borrowers to make suboptimal decisions, relying on repurposed multilateral loans at the expense of long-term investments, on volatile portfolio inflows, and on overburdened domestic banks.

Combining local- and foreign-currency debt in the external DSA leads to bad incentives, encouraging unnecessary domestic restructurings or constraining the development of domestic capital markets which is otherwise supported by the IMF and development partners.

Domestic-currency and foreign-currency debts are different beasts. Nonresident holdings of local-currency debt do pose risks to the external position but usually through a potential drain on foreign reserves if investors exit their position, rather than the forecasted maturity redemptions: the speed of in- and outflows, as well as exchange rates swings, in frontier domestic debt markets make it almost irrelevant to have forecasts for the drain on reserves in more than 2-3 years.

Instead of including NRH in the external DSA, a possibility could be to have a separate stress test gauging the risks of short-term outflows compared to the country’s foreign reserves. Alternatively Brad Setser also proposed two ways to window dress IMF targets, by assuming that NRH are either rolled-off or rolled-over indefinitely, to avoid the “double pain” of recurring interest payments and principal redemptions. This debate could become an important part of the upcoming update of the IMF-WB’s LIC-DSF, expected to start this year.

Communication is key, not just from country authorities but also from the IMF and external creditors. If the government is alone in insisting that a domestic restructuring is off the table, domestic market participants can assume that the IMF and creditors are still pushing the opposite and will prevail in the end. When stress starts building in the domestic debt market, an ad hoc communication from relevant creditor committees could go a long way in alleviating market disruptions.

I am grateful to Godfrey Mwanza, Brad Setser and Teal Emery for valuable comments.

If you want to discuss this further, please reach out: tmaret@globalsov.com

You can also follow me on twitter @TheoMaret

Views expressed here are my own, not my employer’s.