Zambia: Third Time’s a Charm?

Zambia reached an agreement with a steering committee of investors to restructure its three outstanding eurobonds, more than three years after defaulting. Two initial agreements were rejected in November, once by the IMF and twice by the Official Creditor Committee (OCC), causing fears of a complete deadlock and a meltdown of the Common Framework — we discussed this comparability conundrum back then with Brad Setser at the FT’s Alphaville.

It appears however that this bond restructuring agreement will stick — the press release indicates that “The Government has received confirmation that the agreed terms are compatible with the OCC's assessment of comparability of treatment and are compatible with IMF's program parameters under the Second Review framework.”

Time will tell what precisely enabled the updated deal to obtain the OCC’s stamp of approval, especially China’s, since the grievances last year appeared linked to a complex mix of issues — disagreement on the PV reduction for the bonds, misunderstandings around indicative restructuring terms circulated earlier, and the treatment of Chinese commercial banks.

For now we can already dive into the announcement, drawing some lessons for the restructuring architecture and other ongoing cases.

Bond terms: what changed since November?

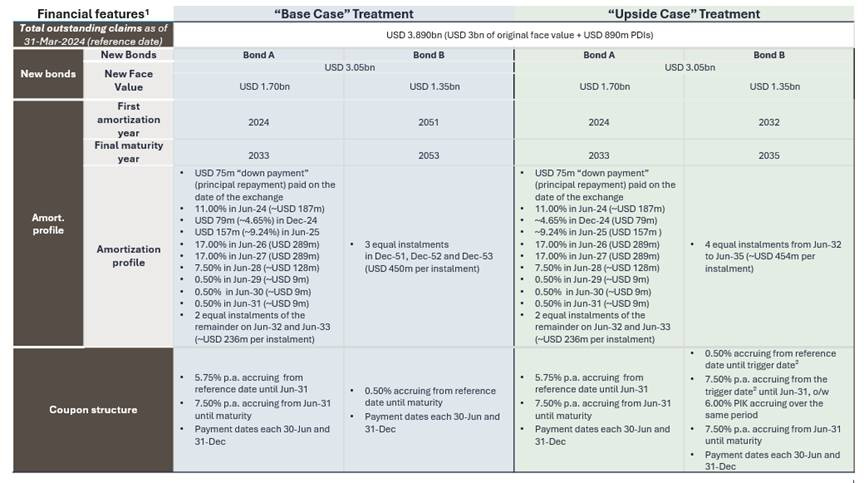

A side-by-side comparison of the agreement cleansed in November and the final deal gives some insights into the adjustments made over the past few months to pass the CoT test — namely a higher principal haircut compensated in part by a steeper amortization.

For starters, the structure of the agreement has not changed, with a fixed income leg (Bond A) and a contingent instrument (Bond B) which starts as a zero-coupon bond maturing in 2053 and can turn into a coupon-paying bond maturing in 2035 if Zambia outperforms IMF forecasts. The dual trigger also stays the same, based either on the IMF’s debt-carrying capacity or on export/revenue projections — though the reference point is now the IMF program’s second review.

The main change compared to the November version relates to the reduction of the face value of Bond A by $150m. Back in November the CoT issue was mostly in the baseline — not the upside scenario — so one could have expected a reweighting of the two bonds keeping the total face value constant, but the face value of bond B stays at $1.35bn.

The larger principal haircut arguably contributes to an increase of the PV reduction, which was apparently the main sticking point in the CoT assessment last year. An important question is the date at which the OCC will fix the CoT calculations — the bonds accumulated $70m in past due interest since November, which can artificially increase the PV haircut if the OCC calculates it at the time of the exchange instead of a common time for all creditors.

In addition to the larger haircut, there have been slight adjustments to the coupons, with the coupon of Bond A decreasing slightly in later years and the coupons of Bond B increasing in the upside scenario only — this arguably contributes also to a reduction of the present value in the baseline.

From the bondholders’ point of view, this larger haircut is compensated in part by a steeper amortization of bond A. Principal payments in 2024-2025 (the remainder of the IMF program) increase slightly from $476m to $498m, but the main change is in the years just after the program: principal payments in 2026-2027 increase from $208m to $578m — by end-2028, 70% of Bond A will have been repaid, leaving just $500m outstanding to avoid the removal of the bond from the main EM indices before maturity.

These payments in 2026-2027 hence appear instrumental in getting the deal over the line, so it is worth asking where the added debt servicing capacity came from — the rejected November deal already saturated available cash flows within the IMF targets. A first option is that the November deal was based on the macro-fiscal framework of the first review, and adjustments during the second review could have increased Zambia’s ability to service debt. However a quick look at the projections in the tables of these two reviews shows that the export and revenue projections, as well as nonresident holdings of domestic debt, have not moved significantly.

Another option relates to Chinese state-owned banks such as CDB and ICBC. Back in November, it was reported that China feared the bond deal would not leave enough cashflows for these banks — a surprising position since upfront cash usually comes in exchange for face value reductions which Chinese state-owned banks are notoriously reluctant to accept. Hence we can speculate that some of these 2026-2027 cashflows were initially earmarked for Chinese “commercial” banks, and the Zambian authorities progressed towards a restructuring deal with them that implies no principal haircut and a longer maturity extension. This in turn enables Zambia to allocate these cash flows to bondholders, while the Chinese banks might start to be repaid in 2029-2031 when bond amortization coincidently drops to just $9m per year.

Bottom line: ballpark calculations show that the recovery value for the bonds at a relevant market rate did not move much compared to the November deal — a significant drop in exit yields will probably do some of the heavy lifting here — making the few-month delay and the initial rejection of the deal by the OCC all the more frustrating in hindsight.

It’s all in the fine prints

The more interesting part of the press release relates to the inclusion in the new bonds of various non-financial provisions, which were not mentioned in November. Such non-financial provisions were also discussed in Suriname but it was a specific enough situation to limit the precedent-setting effect — e.g. with oil discoveries and a tight investor base. The ones drafted in Zambia could well end up being used in the other bond restructurings expected to close this year, from Sri Lanka to Ukraine. Therefore it is worth discussing what the precise wording could look like, judging from the indications in the press release.

Most-favored creditor clauses

The new bonds will feature a provision “that will require the Government to ensure certain other creditors do not receive a better recovery in the restructuring on net present value terms”, as per the press release. MFC provisions had been mentioned in policy debates in recent years, hailed by some as a way to “break the sovereign debt impasse”.

Ukraine also provides relevant precedents for these clauses: they had been used in the 2015 restructuring, making it an event of default for Ukraine to settle on better terms with holdouts including on that infamous Russia-held claim. Similarly in the 2022 restructuring of Ukraine’s GDP warrants, a most-favored creditor provision was inserted to limit Ukraine’s ability to make payments during the deferral period to dissenting Eurobonds.

A first important question in Zambia will be the scope covered by the terms “certain other creditors” in the wording of the MFC provision. This arguably does not include official creditors: since they use three formulas to assess CoT, any commercial creditor seeking more upfront cash would have to concede a higher present-value reduction than official creditors. The provision will instead probably target non-bond commercial creditors such as Credit Suisse or Standard Chartered, but more interestingly the state banks that China chose to classify as commercial — CDB, ICBC, BoC, etc. — in which case China’s reaction will be interesting to monitor.

The provision could also ruffle feathers if it targets Afreximbank, which is classified by Zambia as a commercial creditor but has long argued it should benefit from preferred creditor status or at least preferable treatment. This in turn could have an impact on the institution’s rating and funding cost. For instance, Moody’s noted in February 2024 about ongoing restructurings that “Afreximbank could be called on to provide a degree of debt relief, which would weigh on asset performance, although Moody's believes that Afreximbank will likely be treated preferably compared to private-sector creditors.”

Another question is that of the precise calculations — while the wording seems to indicate that the unique indicator will be present value, the choice of discount rate could still tip the scale for certain creditors.

Finally, the question of enforcement: even if non-compliance with the provision is classified as an event of default for the new bonds, it is unclear whether the precise debt treatments of all other commercial creditors will be made public. Chinese banks have been known to include confidentiality clauses in loan agreements (even if not always enforced), while Afrexim could have a strong incentive not to publicize its debt treatment for reasons mentioned above — so far even the comprehensive terms of the official creditors deal and its CoT parameters have not been published.

In some way, the use of MFC provisions by commercial creditors will lay ground for a two-tiered comparability system, with official creditors enforcing their requirements on commercial creditors and commercial creditors on a similar footing among themselves. It seems unlikely that debtors would ever accept to include official creditors in the scope of MFC provisions for political reasons, to avoid creating a reverse comparability that the Paris Club has long rejected and China would arguably not approve.

Transparency provisions

The press release states that the new bonds documents will feature “certain ongoing information delivery requirements by Zambia.” A version of these requirements was featured in Suriname’s 2023 restructuring: the new bonds included a provision requiring the authorities to conduct quarterly investor calls.

These provisions have been discussed in policy debates under various forms. Suriname’s investor calls could be seen as the more innocuous option, while the most ambitious proposals go as far as debt incurrence clauses — making it an event of default for a sovereign to incure liabilities beyond a certain level. Some middle ground could consist in the periodic disclosure by Zambia of all government liabilities, which would coincidently support broader debt transparency efforts.

The biggest point of interest will probably be the enforcement mechanism, namely whether the failure to comply with the disclosure requirements will be considered as an event of default. The precise scope of the requirements, including with regards to contingent liabilities or SOE debt, will also be interesting.

Loss reinstatement provisions

The idea of such a provision is that at least part of the debt relief initially granted by investors would be reinstated — i.e. added back to their claim — in case the country defaults again in a certain time frame. There are several reasons for investors to demand such a provision: they might fear that the debtor country goes on a borrowing binge right after the IMF program, causing a subsequent default. Investors in such cases could even be juniorized by the incurrence of collateralized new debt. Hence the loss reinstatement functions as a stick incentivizing sound debt management by the debtor in the wake of the crisis.

There are precedents for such provisions — namely an Ecuador 2030 bond, issued as part of the 2000 restructuring with a “principal reinstatement provision”. The bond documents indicated that if Ecuador were to default in the ten years following the issuance, the principal of the new bonds would be increased by a certain percentage of the outstanding. The default would have to persist for at least 12 months for the reinstatement to take place, creating an incentive for bondholders to delay the resolution of a subsequent restructuring, as discussed in 2007 by Felix Salmon — this shows the importance of careful wording for Zambia.

Belize introduced a similar provision in its 2013 restructuring, but with a faster time frame than Ecuador since the country had only 30 days to cure a potential default. As discussed by the IMF in a paper, this provision had an impact on Belize’s subsequent restructuring in 2016 — the Fund notes that the consent sollicitation to amend the bond terms was completed just within the 30-day period of the principal reinstatement provision.

A first point with Zambia’s version is that, as per the press release, it will only apply to a default during the IMF program, limiting the scope compared to the precedents. The wording of Zambia’s press release also does not mention “principal reinstatement” but “loss reinstatement”, hinting that the reinstated amounts could be calculated differently than looking simply at the principal haircut. A more agressive version would entail the calculation of the present-value reduction at a certain discount rate and fix this as the nominal amount to be reinstated after a default. A more straightforward version would simply reinstate the old contractual cash flows.

This provision might in theory raise issues related to CoT, since it is not included in the official creditor debt deal (based on public information) — bondholders would be better off in case Zambia defaults again in the next couple years. However, the OCC’s approval of the latest agreement with bondholders might indicate that the scope is narrow enough not to threaten the CoT assessment.

Another reason to look carefully at the way Zambia’s loss reinstatement provision will be drafted is that it will matter for other ongoing restructurings. For instance, it can also be thought of as a way for bondholders to hedge against future uncertainty, which could be economic uncertainty, or related to the sequential aspect of the restructuring. A country can ask bondholders to restructure before official creditors, at the risk of these official creditors later assessing the bond deal is not comparable and another restructuring is needed. The loss reinstatement provision in such cases can help reduce the incentive for investors to simply wait for the uncertainty to dissipate before agreeing to write down their claims.

This situation applies for instance to Ukraine and Ethiopia, which are both expected to restructure their Eurobonds in 2024 amid significant uncertainty related to the economy and the position of official creditors — it is no surprise that a loss reinstatement provision was already mentioned in Ethiopia’s december negotiations when bondholders had to hedge against the double uncertainty of the IMF DSA and the CoT assessment.

What’s next?

While Zambia’s press release indicates that the OCC has signed off on the proposal, it has not yet formally communicated on the matter, as opposed to the IMF. Since Zambia is the first Common Framework case involving significant debt relief, it is the first time official creditors go through this process of CoT assessement. It is unclear for instance whether the final wording of the non-financial clauses could potentially trigger the claw-back embedded in the OCC’s MoU and lead to another rejection of the deal — this, luckily, remains pretty much a distant tail risk.

The drafting of the non-financial clauses can be expected to take anywhere from a few weeks to a few months before the launch of the vote and the bond exchange — it took Suriname almost six months between its agreement in principle with bondholders in May 2023 and the bond exchange, so one can only hope for a quicker resolution in Zambia.

Finally, Zambia will then have to conclude restructuring agreements with all remaining commercial creditors while respecting IMF program constraints, the OCC’s comparability requirement, and the new bonds’ MFC provision. The multiplicity of non-financial clauses, from the ones discussed here to the claw-back clause inserted in the OCC’s MoU, makes it all the more important for the different creditor groups to provide transparency about their own deals.

I am grateful to Greg Makoff for valuable comments.

If you want to discuss this further, please reach out: tmaret@globalsov.com

You can also follow me on twitter @TheoMaret

Views expressed here are my own, not my employer’s.